I grew up in Central Pennsylvania, within walking

I grew up in Central Pennsylvania, within walking  distance of the Letort Spring Run and just a short drive from the Yellow Breeches Creek. Both of these rank among the very best trout-fishing streams in the northeast, and yet I was relatively oblivious to the importance of these waterways–to the health of the aquatic ecosystems in the region, to the native and introduced fish populations within them, and to the sport of fly-fishing in general. Sure, I fished a few times as a kid (didn’t everyone?), but I was a complete novice and, in hindsight, really wish that I knew then what I know now. I certainly regret not fully appreciating that opportunity to learn about aquatic ecology when it was so immediately accessible to me.

distance of the Letort Spring Run and just a short drive from the Yellow Breeches Creek. Both of these rank among the very best trout-fishing streams in the northeast, and yet I was relatively oblivious to the importance of these waterways–to the health of the aquatic ecosystems in the region, to the native and introduced fish populations within them, and to the sport of fly-fishing in general. Sure, I fished a few times as a kid (didn’t everyone?), but I was a complete novice and, in hindsight, really wish that I knew then what I know now. I certainly regret not fully appreciating that opportunity to learn about aquatic ecology when it was so immediately accessible to me.

Fortunately, it’s never too late to learn, and I’m finally ‘getting schooled‘ (pun very much intended) this year–along with hundreds of Maryland children–in the life cycle, habitat requirements, and resources needed to successfully raise young trout, all thanks to a new initiative taking place in Irvine’s all-too-quiet Exhibit Hall. With most in-person classes still on hold, due to rising (yet again) pandemic concerns, the Maryland Chapter of Trout Unlimited (T.U.) has made a quick pivot to Plan B for their increasingly popular Trout in the Classroom program. Since so few schools are able to participate this year, T.U. has selected Irvine as its official host site for a new virtual program which is set to launch in just a few weeks–and will be available for all to see!

Fortunately, it’s never too late to learn, and I’m finally ‘getting schooled‘ (pun very much intended) this year–along with hundreds of Maryland children–in the life cycle, habitat requirements, and resources needed to successfully raise young trout, all thanks to a new initiative taking place in Irvine’s all-too-quiet Exhibit Hall. With most in-person classes still on hold, due to rising (yet again) pandemic concerns, the Maryland Chapter of Trout Unlimited (T.U.) has made a quick pivot to Plan B for their increasingly popular Trout in the Classroom program. Since so few schools are able to participate this year, T.U. has selected Irvine as its official host site for a new virtual program which is set to launch in just a few weeks–and will be available for all to see!

Some background: in the United States, game fish have been artificially propagated in hatcheries since 1870. In fact, there are now several hundred government-sponsored fisheries throughout the country. A major reason for this proliferation is that survival rates are much higher under the controlled conditions of fish hatcheries than they would be in the wild; this is particularly true for salmonids, namely trout. In a cool mountain stream, only roughly 5% of trout eggs would survive to adulthood; in a carefully monitored 55-gallon tank, that figure can jump as high as 75-90%. Beginning in the 1970’s, Canadian fisheries biologists initiated a program in which school children helped raise salmon eggs through their first half-year, then released them into the wild. The program spread to several areas of the western U.S. over the next decade. The first iteration of the current Trout in the Classroom (TIC) program occurred in 1991 in New Jersey. A clear ‘win-win’ for all involved, the program has grown rapidly; there are now roughly 5000 schools that participate, in 35 states. In Maryland alone, over 100 schools–and even a familiar Nature Center(!)–have participated in the past few years.

TIC will work with students ranging from third grade through twelfth. However, the typical target age is somewhere between fourth and seventh grade. The program’s merits are many. It engages students in doing real science, not just reading about it, as they monitor water quality daily–testing temperature (trout need cool water, around 55 to 60o F, in order to thrive), pH (trout are highly sensitive to acid; that’s why they do so well in the alkaline limestone creeks of Pennsylvania), and levels of dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and nitrates. The students learn a great deal about the life cycle of the species they raise; they gain a strong sense of the balance within an aquatic system and an appreciation for the need to have clean water in order to maintain a healthy watershed; and they form a meaningful connection with their local waterways, which fosters a conservation mindset at an early age. And they reap all of these benefits while helping increase the number of trout available for recreational fishing in Maryland’s waterways . . . what’s not to like?!?

TIC will work with students ranging from third grade through twelfth. However, the typical target age is somewhere between fourth and seventh grade. The program’s merits are many. It engages students in doing real science, not just reading about it, as they monitor water quality daily–testing temperature (trout need cool water, around 55 to 60o F, in order to thrive), pH (trout are highly sensitive to acid; that’s why they do so well in the alkaline limestone creeks of Pennsylvania), and levels of dissolved oxygen, ammonia, and nitrates. The students learn a great deal about the life cycle of the species they raise; they gain a strong sense of the balance within an aquatic system and an appreciation for the need to have clean water in order to maintain a healthy watershed; and they form a meaningful connection with their local waterways, which fosters a conservation mindset at an early age. And they reap all of these benefits while helping increase the number of trout available for recreational fishing in Maryland’s waterways . . . what’s not to like?!?

It should be noted that all of the fish eggs that TIC delivers to schools are triploid, which means the eggs have a third set of chromosomes and will result in sterile fish. Triploidy does not involve genetic engineering of any kind; it simply involves heating or pressurizing the eggs so that they retain a third chromosome which would otherwise be expelled after fertilization. Triploid trout, by virtue of not being able to reproduce, tend to grow a bit faster and larger and there is no worry about diluting genetic diversity or creating new breeders which might outcompete the remaining wild brook trout populations in the East.

In Maryland and in many parts of Pennsylvania, the schools participating in TIC are raising rainbow trout. Originally native to extreme western North America, rainbows are a hearty species, relatively disease-resistant, and easy to raise. (Note: Only brook trout are native to the Eastern U.S.; rainbows and brown trout are introduced species that have done so well here that many of their populations are now self-sustaining. Still, due to the popularity of fly-fishing for these species, most local waterways continue to be stocked with them annually.

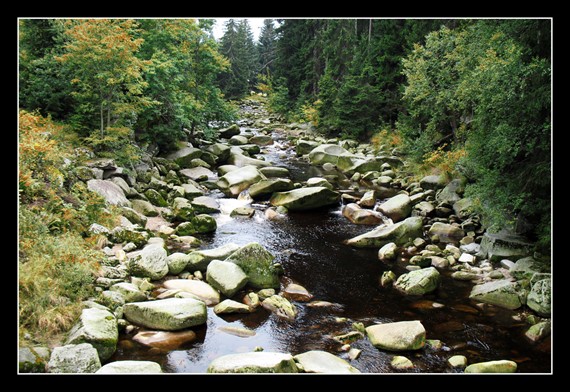

are raising rainbow trout. Originally native to extreme western North America, rainbows are a hearty species, relatively disease-resistant, and easy to raise. (Note: Only brook trout are native to the Eastern U.S.; rainbows and brown trout are introduced species that have done so well here that many of their populations are now self-sustaining. Still, due to the popularity of fly-fishing for these species, most local waterways continue to be stocked with them annually. ) Rainbows are particularly prized, both for their taste and for the sheer challenge of catching them. They can be difficult to lure and put up quite a struggle when hooked; rainbows are not easy bounty for inexperienced anglers. Given their popularity, Maryland hatcheries raise roughly half a million rainbow trout annually and release them into more than 100 streams. One of the very best places to fish for them is in the Big Gunpowder Falls, just a few miles up I-83 from Hunt Valley. Rainbows flourish in shallow, well-oxygenated tributaries that have gravel bottoms and ample natural cover (fallen logs, large rocks, etc.) Even though they are primarily surface-feeders, this penchant for narrow streams with plenty of vegetative shelter certainly contributes to their reputation as a challenging catch.

) Rainbows are particularly prized, both for their taste and for the sheer challenge of catching them. They can be difficult to lure and put up quite a struggle when hooked; rainbows are not easy bounty for inexperienced anglers. Given their popularity, Maryland hatcheries raise roughly half a million rainbow trout annually and release them into more than 100 streams. One of the very best places to fish for them is in the Big Gunpowder Falls, just a few miles up I-83 from Hunt Valley. Rainbows flourish in shallow, well-oxygenated tributaries that have gravel bottoms and ample natural cover (fallen logs, large rocks, etc.) Even though they are primarily surface-feeders, this penchant for narrow streams with plenty of vegetative shelter certainly contributes to their reputation as a challenging catch.

The gravel bottom of streams is where eggs are deposited and the trout life cycle begins. In winter or very early spring, when water temperatures are low and, hence, dissolved oxygen levels are at their highest, the female uses her tail to clear a nest area, known as a redd, and proceeds to deposit about 1000 eggs for every pound she weighs. (A typical adult rainbow weighs between two and eight pounds and measures approximately 8-14 inches in length, although they occasionally attain much greater size.) A male immediately deposits milt, containing sperm, onto the eggs, and the female then brushes gravel over top of the fertilized roe for protection. In roughly 5 to 7 weeks, the eggs hatch and tiny alevin emerge. For the first few weeks of their life, the hatchlings remain near the nest and live off of the yolk sac that is still attached to their bodies. Thereafter, the small troutlings enter the fry stage, during which they subsist mostly on zooplankton. Within a few months, when they reach several inches in length, they become known as fingerlings–a reference to their size, relative to an average human hand. At this point their diet begins to diversify, with aquatic insects and their larvae representing a large portion.

The gravel bottom of streams is where eggs are deposited and the trout life cycle begins. In winter or very early spring, when water temperatures are low and, hence, dissolved oxygen levels are at their highest, the female uses her tail to clear a nest area, known as a redd, and proceeds to deposit about 1000 eggs for every pound she weighs. (A typical adult rainbow weighs between two and eight pounds and measures approximately 8-14 inches in length, although they occasionally attain much greater size.) A male immediately deposits milt, containing sperm, onto the eggs, and the female then brushes gravel over top of the fertilized roe for protection. In roughly 5 to 7 weeks, the eggs hatch and tiny alevin emerge. For the first few weeks of their life, the hatchlings remain near the nest and live off of the yolk sac that is still attached to their bodies. Thereafter, the small troutlings enter the fry stage, during which they subsist mostly on zooplankton. Within a few months, when they reach several inches in length, they become known as fingerlings–a reference to their size, relative to an average human hand. At this point their diet begins to diversify, with aquatic insects and their larvae representing a large portion.  At some point during the fry-to-fingerling transition, the young fish develop dark vertical bars down their sides, known as parr marks; these tend to signify that the final juvenile phase of the life cycle has begun. Over the next year, these parr marks fade and are replaced with the more familiar adult coloration. Not until they are two years old are trout full adults, capable of reproducing and starting the cycle over again. As they near adult size, they continue to vary their diet, eating small fish and crustaceans, and even scavenging on fish carcasses found in the water. Throughout, however, aquatic insects make up a significant portion of their intake and, of course, provide the basis for the dynamic of fly-fishing. It is worth noting that during the COVID-19 pandemic, fishing (along with other forms of outdoor recreation) has seen a surge in popularity, as a healthy way to engage with nature while remaining socially distanced.

At some point during the fry-to-fingerling transition, the young fish develop dark vertical bars down their sides, known as parr marks; these tend to signify that the final juvenile phase of the life cycle has begun. Over the next year, these parr marks fade and are replaced with the more familiar adult coloration. Not until they are two years old are trout full adults, capable of reproducing and starting the cycle over again. As they near adult size, they continue to vary their diet, eating small fish and crustaceans, and even scavenging on fish carcasses found in the water. Throughout, however, aquatic insects make up a significant portion of their intake and, of course, provide the basis for the dynamic of fly-fishing. It is worth noting that during the COVID-19 pandemic, fishing (along with other forms of outdoor recreation) has seen a surge in popularity, as a healthy way to engage with nature while remaining socially distanced.

So, back to Irvine . . . with winter soon upon us, spawning season is nearing. In ‘normal’ years, right about now volunteers with Trout Unlimited would be helping schools set up large fish tanks, equipping them with coolers to lower the water temperatures, and preparing to deliver each school a batch of 100-200 trout eggs to care for over the next five months, until the surviving parr are ready to be released into the wild. However, most school children are learning remotely this year and can’t have a normal Trout in the Classroom experience. The Maryland Chapter of T.U. has decided that a virtual TIC is the next best alternative, and they have overhauled their entire website with an entire section devoted to this new format. Under the watchful eye of Animal Caretaker Jenna Krebs and Naturalist Diana Roman, Irvine participated in TIC for the first time in 2019 and experienced an exceptionally high success rate of 90%! Three of the yearlings remain in our tank at Irvine, but the others were all released into Morgan Run, in Carroll County, at the end of April. (See video of that release here.) Based on this success and our plans to participate again this year, even while our Exhibit Hall remains closed to the public, T.U. asked us if we’d be interested in livestreaming the growth and development of this year’s young fish so that school children all over Maryland can still tune in and learn about the program, the species, and the underlying biological issues involved in raising Rainbow Trout from eggs to releasable parr. Of course, we were honored! Our new ‘fish cam‘ has already been set up and is currently being tested in a temporary position; soon it will be wall-mounted and broadcast far and wide. We have been told to expect this year’s batch of eggs sometime in January. Jenna is already writing scripts for a series of educational videos she will be producing . . . it’s all very exciting! You’ll definitely want to tune in this winter and check on the progress of our little indoor fish farm. If you’re like me, I know you’ll learn a lot in the process! –BR