Don’t know how many of you have perused cornell’s BirdCast website recently, but they had a very disturbing video on there last week.

Seems that a confluence of several unfortunate EVents led to a tragedy that would make any nature lover cringe.

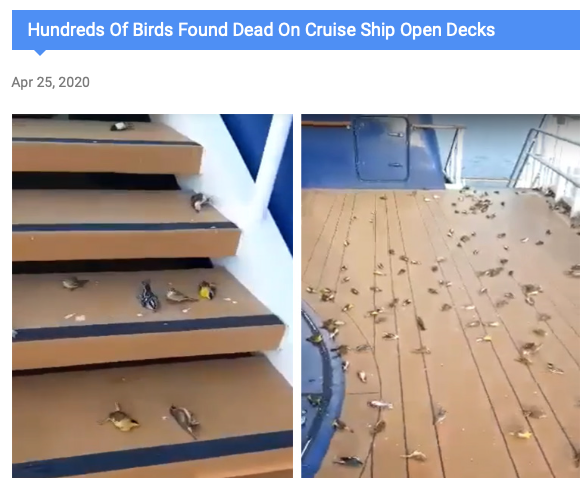

Apparently on the night of April 24th a series of slow-moving storms southeast of Florida happened to push large numbers of migrating songbirds farther out into the Caribbean than usual. This, of course, led to the birds having to work harder and for a longer duration to reach land. Weary and eager to stop and refuel, the birds somehow became confused and disoriented by the lights of an idle cruise ship (one of many during the current pandemic!) out in the water and actually collided with the ship, flying at full speed. Many hundreds (or more) were found dead, littered all over the decks of the ship early the next morning. Most of them were tiny, brilliantly colored warblers, including numerous Common Yellowthroats, Black-throated Blues, and American Redstarts. The site so disturbed one cruise line employee that he/she posted the anonymous video on social media to make others aware of the ornithological tragedy. The exact location and timing of the sad event is still unknown.

Sadly, this type of event is not unusual in our modern world. The evolutionary tactic of migration, which is a survival strategy employed by not only thousands of species of birds, but also bats, bison, blue crabs, butterflies, caribou, sharks, and many whales, among other creatures, has never tested nature’s resilience more than today. Long-distance travel evolved as a way to compensate for seasonal changes in food supply, shelter, and weather conditions. Despite the many dangers that migrants meet along the way, like running into sudden storms or encountering new types of predators in unfamiliar lands, for a significant portion of the world’s wildlife this nomadic existence proved safer than risking freezing or starvation by staying put–until recently, perhaps.

When I speak to well-meaning friends about events like the recent mass mortality of migrating warblers on that ship, they often respond with a rather anthropocentric, “Well why would flying birds not recognize that’s a ship?” (In other conversations, the word ship has been replaced with car, plane, windmill, satellite tower, and, most often, window pane. And, no, I’m not making this up; I’ve heard every one of these.) Hmmm . . . now let’s think about that for a moment. On the one hand, we have wild animals whose ancestors developed large-scale migratory routes as a critical strategy for survival hundreds of thousands, if not MILLIONS of years ago. On the other end of these collisions are massive skyscrapers, huge machines flying thousands of feet in the air, wheeled vehicles whizzing around at speeds twice as fast as most birds’ cruising speeds. None of these things existed prior to the last century or so! They were never factors in the adoption of migratory lifestyles by much of the world’s wildlife. Never mind the fact that while we upright-walking contradictions prefer to live sealed up from the natural world around us, we also infuse our domiciles with transparent glass so that we can at least see what we are missing on the outside. It doesn’t occur to us that the organisms on the other side of that glass don’t know anything about it, can’t recognize reflections from the real thing, and are so small and quick that almost any collision with a window pane will lead to severe trauma or, likely, death.

Selfishly, we have created a modern world through which other species are finding it increasingly difficult to navigate. Some bird-related statistics (and links to interesting relevant websites):

- After habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation, the second leading cause of death among wild birds is now believed to be feral cats. It is estimated that

free-roaming cats and pet cats that are allowed outside kill somewhere between two and three BILLION birds a year . . . in the U.S. alone. This means that roughly 1 in 4 birds will die at the paws of a cat! Incredibly, felines catch four or five small mammals for every bird that they kill.

free-roaming cats and pet cats that are allowed outside kill somewhere between two and three BILLION birds a year . . . in the U.S. alone. This means that roughly 1 in 4 birds will die at the paws of a cat! Incredibly, felines catch four or five small mammals for every bird that they kill.

- Another 600 million North American birds meet their fate flying into windows. This averages out to almost twenty birds every second! The problem is

especially bad in urban areas, where tall buildings are often designed with huge amounts of glass. What’s worse . . . much of the carnage is avoidable. Because most birds migrate at night and many navigate by the stars, tall buildings or towers that are lit up tend to confuse and disorient birds, especially during conditions of fog or low cloud cover. Starting with Toronto’s FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program) in 1991, over 20 major cities around North America now have their own ‘LIGHTS OUT’ groups of concerned citizens, who not only lobby for city lights to be turned off during peak migration times, but who wake up at the crack of dawn to collect and inventory the many casualties, before city street sweepers do away with the evidence. As awareness has grown, even the initial protocol of the annual 9/11 tribute lights at Ground Zero in Manhattan has been altered, as the powerful beams were drawing in large numbers of confused migrants and trapping them in a maze of towering, glass-covered buildings. Our own very active Lights Out Baltimore has been advocating for darkened skies in our area since 2008; in that time they have collected over 5000 victims of window collisions and have successfully rescued, rehabilitated, and re-released about 20% of them.

especially bad in urban areas, where tall buildings are often designed with huge amounts of glass. What’s worse . . . much of the carnage is avoidable. Because most birds migrate at night and many navigate by the stars, tall buildings or towers that are lit up tend to confuse and disorient birds, especially during conditions of fog or low cloud cover. Starting with Toronto’s FLAP (Fatal Light Awareness Program) in 1991, over 20 major cities around North America now have their own ‘LIGHTS OUT’ groups of concerned citizens, who not only lobby for city lights to be turned off during peak migration times, but who wake up at the crack of dawn to collect and inventory the many casualties, before city street sweepers do away with the evidence. As awareness has grown, even the initial protocol of the annual 9/11 tribute lights at Ground Zero in Manhattan has been altered, as the powerful beams were drawing in large numbers of confused migrants and trapping them in a maze of towering, glass-covered buildings. Our own very active Lights Out Baltimore has been advocating for darkened skies in our area since 2008; in that time they have collected over 5000 victims of window collisions and have successfully rescued, rehabilitated, and re-released about 20% of them.

- Cars wipe out another 200 to 300 million birds annually–many of them fairly uncommon species of predators, that hunt at low heights, or scavengers that come to feed by the roadside, only to become a victim themselves. While significant collisions with airplanes are surprisingly uncommon, they tend to receive a great deal of press, since the high speeds involved, particularly during collisions with larger birds like geese, can lead to devastating consequences for the aircraft and the passengers onboard.

- Although the 1972 banning of DDT in the U.S. saved Bald Eagles, Osprey, and Peregrine Falcons from possible extinction, other pesticides still take an enormous toll on today’s birds; estimates show that at least 60-70 million avian deaths are attributable to neonicotinoids and other toxic chemicals being applied to farmlands and lawns.

- Even wind energy, which has often been touted as THE answer for a greener tomorrow and less dependency on fossil fuels, comes with a price.

Roughly half a million birds die colliding with the turning blades of wind turbines, a number big enough that many power companies are starting to alter where they put their turbines (not on mountain ridges along migratory flight paths), whether they light them at night, and whether they even operate them at all during spring and fall nights.

Roughly half a million birds die colliding with the turning blades of wind turbines, a number big enough that many power companies are starting to alter where they put their turbines (not on mountain ridges along migratory flight paths), whether they light them at night, and whether they even operate them at all during spring and fall nights.

- And the list goes on . . . just picture the many images of oil-soaked waterfowl following any offshore spill, photos of pelicans and herons hopelessly entangled in fishing line, or any shot of a seabird, with a plastic six-pack ring ensnared around its neck. We humans have made it impossibly hard to be a bird–or, in fact, almost any wild animal–in ‘our’ world.

How easily we forget that they were here first. And that our fast-paced modern life isn’t just an ‘inconvenience’ for other species, it’s often a death sentence. That’s never more true than during spring and fall migration, when so many species are stretched to their physical limits, traveling thousands of danger-filled miles to repeat a tradition begun millenia ago by ancestors who adopted what was then the safest strategy for survival.

It still pains me to this day to recall one early summer afternoon three decades ago, when I came around a turn on a rural road in Central Pennsylvania a bit too fast. I felt a small thud as I struck a bird that was leisurely flying across to another part of its breeding territory. It all happened so quickly that I hadn’t seen what species it was, whether it had survived, etc. I pulled over and was stunned to find the remains of a gorgeous male Baltimore Oriole plastered to the grill of my car. That little bird had been wintering somewhere in Central America just a month or two earlier and had a return ticket for the fall. To have survived that kind of journey and all of its inherent risks, only to get slammed crossing the street on its own turf, just wasn’t fair. Migratory species have always played a dangerous game, but I fear that we’re increasingly stacking the deck against them, creating a game they simply can’t win. –BR