Heads up! Right now we are entering THE BEST week of the entire year to witness the glorious diversity of songbirds that move through the Mid-Atlantic! Spring migration in this part of the country tends to peak within a few days of May 10th, depending on weather patterns. This is no secret to most amateur ornithologists. Early and mid-May are when hoards of birders flock to places like the green oasis of New York’s Central Park, the peninsula of Cape May, NJ, as well as Ohio’s Magee Marsh and Ontario’s Point Pelee, on opposite shores of Lake Erie. In terms of sheer numbers, there are admittedly a lot more birds to be seen during fall migration than spring, as all of that summer’s nestlings embark on their first major journey south. However, southbound travels tend to be spread out over a broader time frame, with some species leaving their nesting grounds already in early August while others stay until well into October. Spring migration, by contrast, comes in intense ‘waves’ that mostly span just a few weeks from late April through mid-May. Furthermore, most species shed their bright breeding plumage by the end of summer, so colors are far less spectacular in Autumn; also, territorial singing comes to an end with the close of breeding season, so fall birds are just vastly more difficult to detect. Never mind the additional complication of each falling leaf distracting the attention of birders, whose eyes are trained to scrutinize for even the smallest bit of motion among the tree branches! There’s no question that it’s far more appealing to go out and look for brightly colored, loudly singing birds prior to full leaf-out–especially after the gray, quiet months of winter have recently passed.

In terms of sheer numbers, there are admittedly a lot more birds to be seen during fall migration than spring, as all of that summer’s nestlings embark on their first major journey south. However, southbound travels tend to be spread out over a broader time frame, with some species leaving their nesting grounds already in early August while others stay until well into October. Spring migration, by contrast, comes in intense ‘waves’ that mostly span just a few weeks from late April through mid-May. Furthermore, most species shed their bright breeding plumage by the end of summer, so colors are far less spectacular in Autumn; also, territorial singing comes to an end with the close of breeding season, so fall birds are just vastly more difficult to detect. Never mind the additional complication of each falling leaf distracting the attention of birders, whose eyes are trained to scrutinize for even the smallest bit of motion among the tree branches! There’s no question that it’s far more appealing to go out and look for brightly colored, loudly singing birds prior to full leaf-out–especially after the gray, quiet months of winter have recently passed.

←Northern Cardinal Dark-eyed Junco→

←Northern Cardinal Dark-eyed Junco→

In all, Maryland is home to just over 300 species of birds, from among the roughly 800 species native to the U.S. These generally fall into four groups–residents (like the Northern Cardinal) which live here year-round, winter visitors (like the familiar Dark-eyed Junco or, colloquially, snowbird) which spend the colder half of the year in our region but head to northern climes for summer breeding, the much more common summer breeders (like our state bird, the Baltimore Oriole), which raise their young here then head to more tropical regions for the winter, and there’s also a significant number of predictable migrants (like the gorgeous tree-top dwelling Blackburnian Warbler) which pass through our state each spring and fall enroute to/from their nesting grounds within the vast forests of northern New England and Canada. Of course, with our close proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the many unique habitats along our squiggly shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay, Maryland gets its share of rarities that show up from time to time, but there are about 300 species that can be reliably found on an annual basis.

←Baltimore Oriole by Laura Bankey Blackburnian Warbler by Emily Stanley →

Of these, a little over half are waterfowl, raptors, herons, gulls, or shorebirds–all of which travel on different schedules and to differing extents. That leaves about 125 species of ‘Passerines’ (perching birds), including the ones most of us know from our backyards, as well as those less common species that can be found deeper in forested areas or extensive farmland. Aside from a few dozen species of residents and even fewer winter visitors, the majority of these smaller birds are migratory and are returning to or passing through our area RIGHT NOW. If you have even a hint of interest in witnessing their journey, go for an early morning walk at the edge of any wooded area in the next few days; pause quietly, look up, and take in the flitting activity, bright colors, and sweet songs of these fascinating travelers. Most of them are no bigger than a candy bar, yet are in the process of flying thousands of miles just because it is a more successful strategy for them than to attempt surviving a prolonged winter of cold temperatures and little food availability. It’s a mind-blowing evolutionary strategy.

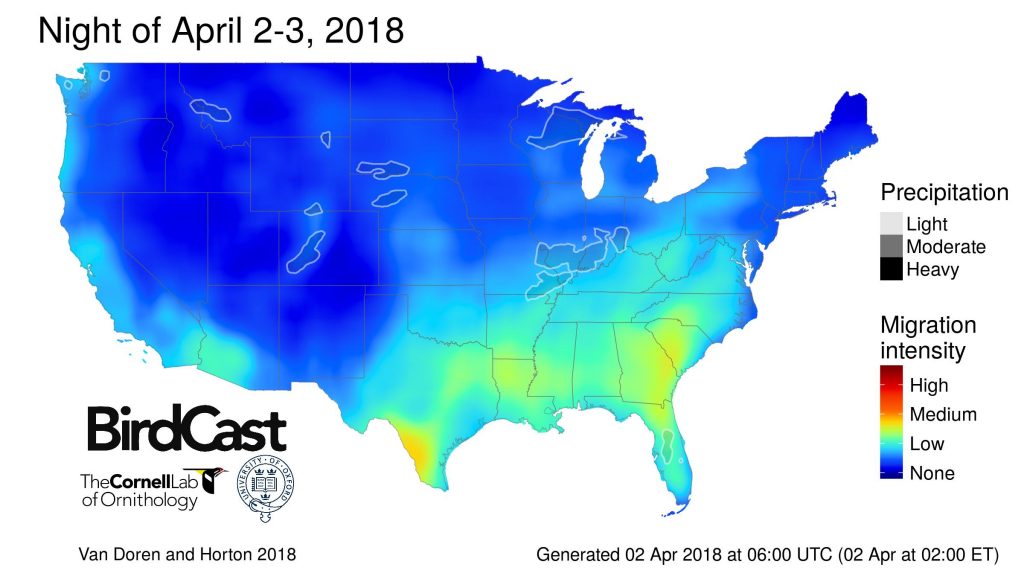

However, thanks to modern technology, you can now track the phenomenon of migration without even leaving your armchair–not that I’m endorsing you skip the outdoor bird walks . . .

What is perhaps even more boggling than the journey that these tiny winged creatures make twice a year is the timing of when they do it. For a number of reasons, among them less visibility to predators, less ‘heat exhaustion,’ and, perhaps, less chance of severe weather, most bird migration takes place at night. Scientists are still grappling with many of the how’s and why’s of it, but they do know that the stars play a key navigational role in getting birds where they need to go. Thus, migration flights are more intense on clear nights. And this explains, in part anyway, why bird activity is at its highest early in the morning, when birds are engaged in a re-fueling feeding frenzy after flying all night, then drops off midday as birds get a little R&R, and increases again shortly before dusk, when they top off the tank prior to hitting the skyways again.

What is perhaps even more boggling than the journey that these tiny winged creatures make twice a year is the timing of when they do it. For a number of reasons, among them less visibility to predators, less ‘heat exhaustion,’ and, perhaps, less chance of severe weather, most bird migration takes place at night. Scientists are still grappling with many of the how’s and why’s of it, but they do know that the stars play a key navigational role in getting birds where they need to go. Thus, migration flights are more intense on clear nights. And this explains, in part anyway, why bird activity is at its highest early in the morning, when birds are engaged in a re-fueling feeding frenzy after flying all night, then drops off midday as birds get a little R&R, and increases again shortly before dusk, when they top off the tank prior to hitting the skyways again.

Since most of their travels occur under the cover of darkness, many of the specifics of avian migration are just being studied; there’s still plenty to learn. But, fascinatingly, much of the mystery has begun to unfold, thanks to, of all things, World War II RADAR technology! First developed to detect enemy aircraft, radar (the Naval acronym for ‘radio detection and ranging’) was soon seen as a way to help track and predict weather events. However, in the post-war years, the imaging was messy, as things like smoke from forest fires, large swarms of insects, and (here it comes!) flocks of birds could create ‘clutter’ that pulsed back and clouded the radar. Not until the 1990’s, with the development of ‘NEXRAD’ (next-generation radar), did scientists figure out how to use computers to sort out meteorological phenomena from other airborne clutter–and even to distinguish flying birds from insects from bats from smog. This quickly led to the advent of a new field known as Radar Ornithology. Cornell University’s Lab or Ornithology has become an international leader in bringing this intriguing new science to the public, through their creation of BIRDCAST, a website that is at its most fascinating right now, in the midst of spring migration. Birdcast uses weather radar images from almost 150 locations around the country to produce maps that show IN REAL TIME (and updated every ten minutes!) precisely where the ‘flying biomass’ of birds is heavier or lighter, in which direction the masses are moving, and even rough estimates of the number of birds moving through any given region. Incredibly, in 2018 they added another feature: predictions for the nights ahead! Based on flights from previous years combined with current weather conditions, the Birdcast team actually gives a fairly reliable three-night ‘forecast’ so birders can plan ahead in their forays out to see large numbers of migrants. You simply have to check out Birdcast to believe this innovative use of updated WWII technology to help advance modern science! There’s no better time than the present . . . literally!