Now You See It; now you don’t

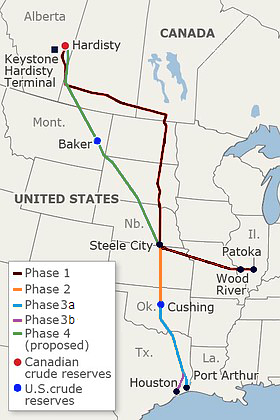

It certainly didn’t take long for frustrated environmentalists to feel grateful for the new administration in Washington. On Joe Biden’s first day as President, among a number of executive orders that he signed was the anticipated move to revoke the permit to construct the fourth (XL) phase of the Keystone Pipeline . . . again. The long-debated extension to the  pipeline system would’ve provided a larger and more direct line from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada to Nebraska, where the transported oil would be sent on, using existing lines, to refineries in Illinois, Louisiana, and Texas. First proposed in 2005 by TransCanada Corporation, the pipeline’s first three phases were built between 2010 and 2016. The XL phase, however, has been on again and off again numerous times over the past six years. The project received initial support in 2015, shortly after the Senate flipped from blue to red. However, late that same year, Secretary of State John Kerry helped convince President Obama to veto it, declaring that it was unnecessary and not in the best interest of the United States. At the time, fracking had recently become the number one domestic source of natural gas and crude oil, lessening, at least temporarily, U.S. dependence on fuels from other countries. Secondly, the extraction of heavy oil from the sands of the midwestern province of Alberta is a complicated, energy-intensive process, which, in itself, leaves a large carbon footprint. Furthermore, as global warming came increasingly to the forefront of international relations, Kerry worried that supporting the expansion of such a major oil pipeline at this time could undermine American leadership in the global war on climate change. Subsequently, however, President Trump revived it during his first week in office, in January of 2017. Since, legal challenges on the state and local level have kept the $7-9 Billion project in limbo for close to three years, and only minimal work has been completed on it thus far.

pipeline system would’ve provided a larger and more direct line from the tar sands of Alberta, Canada to Nebraska, where the transported oil would be sent on, using existing lines, to refineries in Illinois, Louisiana, and Texas. First proposed in 2005 by TransCanada Corporation, the pipeline’s first three phases were built between 2010 and 2016. The XL phase, however, has been on again and off again numerous times over the past six years. The project received initial support in 2015, shortly after the Senate flipped from blue to red. However, late that same year, Secretary of State John Kerry helped convince President Obama to veto it, declaring that it was unnecessary and not in the best interest of the United States. At the time, fracking had recently become the number one domestic source of natural gas and crude oil, lessening, at least temporarily, U.S. dependence on fuels from other countries. Secondly, the extraction of heavy oil from the sands of the midwestern province of Alberta is a complicated, energy-intensive process, which, in itself, leaves a large carbon footprint. Furthermore, as global warming came increasingly to the forefront of international relations, Kerry worried that supporting the expansion of such a major oil pipeline at this time could undermine American leadership in the global war on climate change. Subsequently, however, President Trump revived it during his first week in office, in January of 2017. Since, legal challenges on the state and local level have kept the $7-9 Billion project in limbo for close to three years, and only minimal work has been completed on it thus far.

The XL represents a classic case of jobs vs. the environment, and whether one thinks the risks outweigh the benefits depends largely on which of these two issues one deems more important. In other words, feelings about the XL tend to align quite closely with political party affiliation. Interestingly, most Canadians seem to be in favor of the project, as it would create more than 1000 new jobs in Alberta and make it possible for them to export larger quantities of crude oil more efficiently, with less need for rail and truck transport. Then again, an astonishing 90% of Canadians live within 100 miles of the U.S., leaving them incredibly vast amounts of wilderness to their north–a luxury that Americans do not have. Hence, on the southern side of the border, there seems to be less to gain (aside from short-term construction jobs) and quite a bit more to lose, primarily in terms of the environment. The original plan had the 1179-mile XL running through the eastern third of Montana, where Native Americans have very real concerns about pollution of groundwater supplies, then across a large swath of South Dakota and right through the Sandhills region of northcentral Nebraska. This last section causes the most angst for those with environmental concerns.

of these two issues one deems more important. In other words, feelings about the XL tend to align quite closely with political party affiliation. Interestingly, most Canadians seem to be in favor of the project, as it would create more than 1000 new jobs in Alberta and make it possible for them to export larger quantities of crude oil more efficiently, with less need for rail and truck transport. Then again, an astonishing 90% of Canadians live within 100 miles of the U.S., leaving them incredibly vast amounts of wilderness to their north–a luxury that Americans do not have. Hence, on the southern side of the border, there seems to be less to gain (aside from short-term construction jobs) and quite a bit more to lose, primarily in terms of the environment. The original plan had the 1179-mile XL running through the eastern third of Montana, where Native Americans have very real concerns about pollution of groundwater supplies, then across a large swath of South Dakota and right through the Sandhills region of northcentral Nebraska. This last section causes the most angst for those with environmental concerns.

The Sandhills provide large unbroken areas of very unique habitat. Essentially an enormous area of vegetated sand dunes, the Sandhills have soil that is too poor in quality for farming.  Thus, it is a region of pristine expanses of tall prairie grasses that harbor wildlife like Sharp-tailed Grouse, Greater Prairie Chickens, Kangaroo Rats, and American Badgers, as well as small populations of Pronghorn, Burrowing Owls, and American Bison. All of these species have very specific ecological needs that are best met in tall grassland habitats and difficult to find in other ecosystems. The low-lying areas of the Sandhills happen to form an intricate network of thousands of wetland ponds and shallow lakes, making the region a fabulous stop-over point for millions of waterfowl and, of course, Sandhill Cranes, which migrate through twice a year along the Central Flyway. Beneath the Sandhills lies the heart of the Ogallala High Plains Aquifer, one of the world’s

Thus, it is a region of pristine expanses of tall prairie grasses that harbor wildlife like Sharp-tailed Grouse, Greater Prairie Chickens, Kangaroo Rats, and American Badgers, as well as small populations of Pronghorn, Burrowing Owls, and American Bison. All of these species have very specific ecological needs that are best met in tall grassland habitats and difficult to find in other ecosystems. The low-lying areas of the Sandhills happen to form an intricate network of thousands of wetland ponds and shallow lakes, making the region a fabulous stop-over point for millions of waterfowl and, of course, Sandhill Cranes, which migrate through twice a year along the Central Flyway. Beneath the Sandhills lies the heart of the Ogallala High Plains Aquifer, one of the world’s  largest reserves of freshwater. It provides drinking water for over 2 million people and supports a significant portion of the agriculture of the Midwest. Couple the potential devastation that a major pipeline construction project could wreak on the unique flora and fauna of the Sandhills with the possibility of an environmental disaster in this sensitive region, and many environmentally-minded folks are not willing to take the risk. Likely the clincher was that neighboring South Dakota experienced a 400,000+ gallon leak in another stretch of the Keystone in late 2017; a similar mishap in Nebraska could pollute not only ecosystems that don’t exist anywhere else on so grand a scale, but also the agrarian way of life for a significant portion of Midwesterners. For all of these reasons, we should be thankful that President Biden made it a top priority to shut down construction of the XL for at least the next four years, if not permanently.

largest reserves of freshwater. It provides drinking water for over 2 million people and supports a significant portion of the agriculture of the Midwest. Couple the potential devastation that a major pipeline construction project could wreak on the unique flora and fauna of the Sandhills with the possibility of an environmental disaster in this sensitive region, and many environmentally-minded folks are not willing to take the risk. Likely the clincher was that neighboring South Dakota experienced a 400,000+ gallon leak in another stretch of the Keystone in late 2017; a similar mishap in Nebraska could pollute not only ecosystems that don’t exist anywhere else on so grand a scale, but also the agrarian way of life for a significant portion of Midwesterners. For all of these reasons, we should be thankful that President Biden made it a top priority to shut down construction of the XL for at least the next four years, if not permanently.

* * * * * * * * * *

moth of the marsh

While we’re discussing grassland specialists, there’s a rare local opportunity to observe one of nature’s most stunning winter visitors from the north. The Short-eared Owl is one of the few species endemic to Nebraska’s Sandhills that can also be found in our region, albeit only during the coldest months and with a fair amount of effort. Generally a species of extensive grasslands and marshes, as well as tundra habitats, the Short-ear is the ‘night-shift’ counterpart to the Northern Harrier (formerly known as the Marsh Hawk)–although the owl is less common and, given its crepuscular habits and expertly camouflaged plumage, less frequently encountered.

While we’re discussing grassland specialists, there’s a rare local opportunity to observe one of nature’s most stunning winter visitors from the north. The Short-eared Owl is one of the few species endemic to Nebraska’s Sandhills that can also be found in our region, albeit only during the coldest months and with a fair amount of effort. Generally a species of extensive grasslands and marshes, as well as tundra habitats, the Short-ear is the ‘night-shift’ counterpart to the Northern Harrier (formerly known as the Marsh Hawk)–although the owl is less common and, given its crepuscular habits and expertly camouflaged plumage, less frequently encountered.

Every winter, however, modest numbers of Short-ears move down from Canadian breeding grounds to occupy coastal marshlands and large agricultural areas in the eastern U.S., where the rodent-hunting is far more lucrative. Like their Long-eared cousins, these owls tend to be social, particularly in winter; thus, while encounters don’t come easily, where there’s one, there are often several. At the moment, there are 5 or 6 of them (a goldmine for owl-seekers!) being seen reliably, almost every evening, just five miles over the Mason-Dixon line, right up I-83.

The Hopewell Area Recreation Complex (HARC) outside Stewartstown, PA, is a fascinating and unusual grassland habitat that has rapidly become one of the region’s best birding sites over the past decade. It sits atop a long-closed sanitary landfill, which was operated by the York County Solid Waste Authority form 1974 through 1997, then capped in 1998. Following  a period of government-mandated remediation work to clean up low-level groundwater pollution caused by leaching from the fill, York County converted 200 acres of the site into parkland in 2007. Roughly 1/3 of that is now ballfields used for County recreation programs, but the rest became planned wildlife habitat, specifically designed for the handful of grassland bird species that have gradually disappeared from the Commonwealth as farming practices have changed over the past half century. A pleasant one-mile loop traverses the meadow habitat, and there are bird-viewing platforms at both the roadside trailhead and the half-way point, which were added by the York Audubon Society. An eBird hotspot, HARC has an impressive list of 162 bird species reported (not shabby for a place that was a county dump a few decades ago) and has become the best place to find grassland birds anywhere in southcentral PA — or the Maryland Piedmont, for that matter. In addition to the Short-ears, HARC hosts wintering Harriers and Horned Larks; American Kestrels, Savannah Sparrows, and Eastern Meadowlarks can be found year-round; Grasshopper Sparrows are common breeders, as are Red-headed Woodpeckers, which inhabit the dead snags around the perimeter of the property. A few summers back, midwestern Dickcissels nested at HARC, an unusual occurrence anywhere in the Mid-Atlantic. All of these species are difficult to find in the Baltimore area, but not twenty-five miles up I-83.

a period of government-mandated remediation work to clean up low-level groundwater pollution caused by leaching from the fill, York County converted 200 acres of the site into parkland in 2007. Roughly 1/3 of that is now ballfields used for County recreation programs, but the rest became planned wildlife habitat, specifically designed for the handful of grassland bird species that have gradually disappeared from the Commonwealth as farming practices have changed over the past half century. A pleasant one-mile loop traverses the meadow habitat, and there are bird-viewing platforms at both the roadside trailhead and the half-way point, which were added by the York Audubon Society. An eBird hotspot, HARC has an impressive list of 162 bird species reported (not shabby for a place that was a county dump a few decades ago) and has become the best place to find grassland birds anywhere in southcentral PA — or the Maryland Piedmont, for that matter. In addition to the Short-ears, HARC hosts wintering Harriers and Horned Larks; American Kestrels, Savannah Sparrows, and Eastern Meadowlarks can be found year-round; Grasshopper Sparrows are common breeders, as are Red-headed Woodpeckers, which inhabit the dead snags around the perimeter of the property. A few summers back, midwestern Dickcissels nested at HARC, an unusual occurrence anywhere in the Mid-Atlantic. All of these species are difficult to find in the Baltimore area, but not twenty-five miles up I-83.

If you go to observe the owls, be patient, as they tend to come out 5-15 minutes after the sun sets, just as dusk is settling in. They appear seemingly out of nowhere, as they often rest on the ground, hidden from view among the tall grasses. As the first one begins to take flight, the others promptly join, and for a brief period, there’s a  wonderful show as they gracefully swoop just feet above the ground, in search of small mammal prey. As a former landfill, the site has a series of passive methane venting pipes, which rise, a bit like candy canes, five feet or so out of the ground; these–and the occasional bluebird boxes scattered around the property–act as ideal perches on which the owls will pause to wolf down their catches or to rest briefly before taking off for the next hunt. If you’ve never seen a Short-ear fly, it’s spectacular! Of course, their flight is silent but it also appears completely effortless. With long, broad wings and an irregular, slow rhythm, the flight seems more moth-like than avian; the deep wingbeats are graceful in ways that other birds cannot replicate, and one can only marvel at the agility with which Short-ears turn on a dime to hunt small prey beneath them. It truly is a sight to behold. Do be sure to bundle up! There are no trees to block the wind, and the walk around the grassland loop always feels 5-10 degrees colder than the surrounding area. And don’t hesitate . . . the owls tend to leave the Mid-Atlantic by early March, and there’s no guarantee that they’ll continue their nightly hunts at HARC until then. However, there’s been a remarkably consistent string of sightings at dusk for the past few weeks, giving some predictability to a species that simply isn’t observed often by most birders and, once witnessed, remains truly unforgettable. –BR

wonderful show as they gracefully swoop just feet above the ground, in search of small mammal prey. As a former landfill, the site has a series of passive methane venting pipes, which rise, a bit like candy canes, five feet or so out of the ground; these–and the occasional bluebird boxes scattered around the property–act as ideal perches on which the owls will pause to wolf down their catches or to rest briefly before taking off for the next hunt. If you’ve never seen a Short-ear fly, it’s spectacular! Of course, their flight is silent but it also appears completely effortless. With long, broad wings and an irregular, slow rhythm, the flight seems more moth-like than avian; the deep wingbeats are graceful in ways that other birds cannot replicate, and one can only marvel at the agility with which Short-ears turn on a dime to hunt small prey beneath them. It truly is a sight to behold. Do be sure to bundle up! There are no trees to block the wind, and the walk around the grassland loop always feels 5-10 degrees colder than the surrounding area. And don’t hesitate . . . the owls tend to leave the Mid-Atlantic by early March, and there’s no guarantee that they’ll continue their nightly hunts at HARC until then. However, there’s been a remarkably consistent string of sightings at dusk for the past few weeks, giving some predictability to a species that simply isn’t observed often by most birders and, once witnessed, remains truly unforgettable. –BR