Visit any of the world’s great art museums, symphony halls, opera theaters, or architectural gems, and you will stand among the masses, who are struggling to comprehend the creativity and brilliance of the human mind and the masterpieces that have sprung from it. With all due respect to the vision, talent, and genius of history’s artistic giants, personally I have always found myself more awestruck not by the profound inventions of human intellect, but by the wonders of the natural world and its abundance of incredibly unique adaptations–both physical and behavioral–which help species survive under all sorts of extreme conditions. These are not fictional beasts of human contrivance–unicorns, mermaids, dragons, griffins, ogres–these are real living organisms. They’re not a notion from someone’s imagination; in fact, their unique specializations are beyond imagination. I, for one, am so grateful that Mother Nature and her partner, Evolution, have shaped extraordinary masterpieces which far surpass in complexity, originality, and efficiency any invention of the human brain. To me, learning about them is one of life’s most fulfilling intellectual pursuits and serves as a constant reminder that we, as a species, are but one piece in this great puzzle of life. In the words of Sir David Attenborough, who recently turned 95 years old, “It seems to me that the natural world is the greatest source of excitement; the greatest source of visual beauty; the greatest source of intellectual interest. It is the greatest source of so much in life that makes life worth living.” I couldn’t agree more; when it comes to the miracles of nature, you just can’t make this stuff up.

What finer example of the genius of nature than the noisy insects who have literally taken over our neighborhoods these past few weeks? What could be more unique than the lifecycle of the periodical cicada (genus Magicicada)? The fact that most of their existence takes place well out of our sight leaves much of it a mystery, even to the world’s top entomologists! The strategy by which periodical cicadas survive from one generation to the next is laughable in its simplicity and astonishing to witness. And the fact that they are here and large and slow and can be picked up and observed first-hand allows us a brief sublime window into something which would sound like pure fantasy, if one were only to read about it as some distant phenomenon in a faraway land. We’re actually living it, and it’s fascinating to behold.

Talk about bizarre . . .

Consider the following 20 highly unusual factoids about cicadas–some of which are animated quite nicely in this article:

- Newly hatched cicada nymphs are as small as grains of rice,

Photo by Elias Bonaros.

yet they are designed to be digging machines and eventually burrow down five or six feet into the soil.

- With their 17-year lifespans, our Brood X cicadas are among the longest-lived insects in the world. However, what we see in adult cicadas is less than 0.5% of that lifespan! Almost 99% of a cicada’s life is spent underground in its larval stage.

- During all that time, a cicada nymph will only molt–or shed its exoskeleton–four times, increasing its body size dramatically with each shed.

- These larvae don’t really eat; they drink. Their beak-like mouthparts resemble a straw, through which they suck the sap from tree roots.

- Cicadas tend to avoid evergreen trees, as their sap is to viscous for them to suck.

- While there are over 3000 species of cicadas worldwide, most are NOT periodical. In fact, periodical cicadas are almost exclusively found only in the eastern half of North America. Of the fifteen species of Periodical Cicada found on our continent, all have either a 13- or 17-year lifecycle. These prime numbers are believed to provide an evolutionary advantage, as they’re large enough that no predator can evolve to subsist solely on them. (Most predator species have relative population spikes every two to five years; these will never synchronize with large prime numbers, which are not divisible by them. Yes, it’s a math thing!)

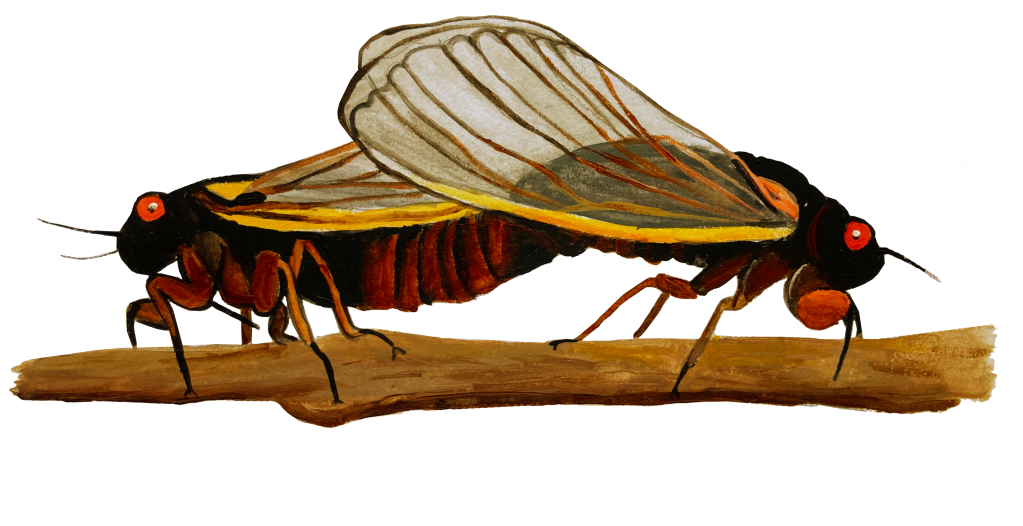

- Our Brood X cicadas are actually 3 different species whose cycles have, over time, coincided. The species can be told apart by the presence or absence of orange banding on their undersides and also by size; I found all three species in the Irvine parking lot just yesterday.

- How do underground nymphs know when 17 years have passed? Good question! Scientists believe it has to do with seasonal changes in the composition and consistency of the tree sap on which they dine, but the exact mechanism is not known.

- Cicadas emerge from the ground when the soil temperature (about 8 inches down) reaches 64o F. How do they recognize this temperature? Again, we do not know for sure. But the process is highly accurate; the cold spell we had in late April and early May this year delayed their emergence by almost two weeks. Cicadas near sunny forest edges emerged several days before those in shadier, interior sections of woods.

- Adult cicadas barely eat. They do suck small amounts of liquid from twigs, but devote

almost all of their four-week adulthood to the process of finding a mate and reproducing.

almost all of their four-week adulthood to the process of finding a mate and reproducing.

- Adult cicadas have five eyes–the two large red ones which are so obvious but also three smaller photoreceptors (called ocelli) on their foreheads. These help the nymphs recognize darkness and light, crucial for burrowing and subsequently emerging from the soil. Five eyes–and yet they still seem to fly into everything!

- The two main eyes are actually white for the first 16 years of a nymph’s life; they only turn red in year 17. Why? Who knows?

- Cicadas have small hooks on their legs, which enable them to cling to vertical surfaces–like the tree trunks on which they tend to shed their exoskeleton for the final time or your shirt when you least expect it!

- Even though they are famously clumsy and awkward as insects go, cicadas undergo a rather remarkable final molt, in which they split the back of their largest nymphal exoskeleton down the middle, then do a Herculean ‘push-up’ to climb out. At this stage, they are at their most tender and vulnerable–much like a soft-shell crab. The newly emerged cicada is called a teneral at this stage and is primarily white and yellow

for a brief time, before the adult shell begins to harden and wings unfurl and dry. It takes almost three days for the adult to reach full development, at which point the insect can fly and climb its way to the treetops where the noise and mayhem of a weeks-long breeding frenzy takes place.

for a brief time, before the adult shell begins to harden and wings unfurl and dry. It takes almost three days for the adult to reach full development, at which point the insect can fly and climb its way to the treetops where the noise and mayhem of a weeks-long breeding frenzy takes place.

- Here in Maryland, we are at peak cicada volume now, in early- to mid-June. The noise generated by a ‘chorus’ of male cicadas trying to attract mates can reach over 100 decibels–louder than a lawn mower and comparable to a chainsaw. In fact, cicadas are the loudest insects on earth; some can be heard from a mile away!

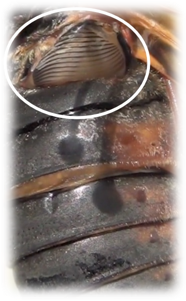

- They are capable of generating such a racket because their ‘singing’

is not a vocalization at all. It is created by the males vibrating two chitinous plates (called tymbals) against their hollow abdomens. While the abdomens of female cicadas are full of reproductive parts and eggs, males’ abdomens are basically empty and designed to amplify sound. (Consider the difference between smacking the side of a full two-liter soda bottle and doing the same when the bottle is empty.)

is not a vocalization at all. It is created by the males vibrating two chitinous plates (called tymbals) against their hollow abdomens. While the abdomens of female cicadas are full of reproductive parts and eggs, males’ abdomens are basically empty and designed to amplify sound. (Consider the difference between smacking the side of a full two-liter soda bottle and doing the same when the bottle is empty.)

- The ovipositor, or tube through which a female lays her eggs,

Periodical cicada female laying eggs into stem. Photo: PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources – Forestry, Bugwood.orgof a female cicada has

evolved a sharp saw-like edge that cuts slits through the bark of young branches. It is in these slits that the female deposits her eggs. The slits cause a deep enough wound to disrupt the flow of nutrients through the xylem and phloem, thus killing off the ends of the branch. This causes the ‘flagging’ we will see on many trees later this summer and is the reason that Irvine (and many cicada-aware gardeners) covered its youngest saplings with fine netting this spring!

Egg laying damage to a tree twig. Photo: Jim Baker, North Carolina State University, Bugwood.org

- While direct predators have proven unable to synchronize their lifecycles with that of periodical cicadas, a fungus has successfully done just that! Massospora cicadina has a story all its own that is every bit as strange and fascinating as the insects that it attacks. Basically, it is a powdery substance which grows quickly and eats away at the abdomens of cicadas (yet, thankfully, is harmless to other species), eventually disintegrating the entire back half of the insect.

Incredibly, males inflicted with the fungus begin to flick their wings and produce a sound similar to the normal mating calls of female cicadas. This actually attracts other males to attempt to mate and, in turn, spreads the fungus to others–making it essentially an STD. Because the fungus actually alters the behavior of male cicadas, it is often referred to as the ‘zombie fungus.‘ The psychedelic fungus, in fact, contains a similar chemical composition to that of certain hallucinogenic mushrooms!

Incredibly, males inflicted with the fungus begin to flick their wings and produce a sound similar to the normal mating calls of female cicadas. This actually attracts other males to attempt to mate and, in turn, spreads the fungus to others–making it essentially an STD. Because the fungus actually alters the behavior of male cicadas, it is often referred to as the ‘zombie fungus.‘ The psychedelic fungus, in fact, contains a similar chemical composition to that of certain hallucinogenic mushrooms!

- By far the most distinguishing feature of the cicada lifecycle is its survival strategy,known simply as predator satiation. With no ability to sting or bite, no

protective armor, and lacking speed, stealth, and agility, cicadas are an easy target for any hungry critter; even box turtles eat them! The way they persist from one generation to the next is simply to exist in such massive quantities that it becomes impossible for ALL of them to be consumed. In peak areas, periodical cicadas exist at a density of roughly 1.5 million per acre. This translates to about 25 per square foot! It also explains why the more squeamish among us are so freaked out by the sheer magnitude of the entire phenomenon; it truly resembles a real-life horror movie (although the bugs pose absolutely no danger whatsoever.)

protective armor, and lacking speed, stealth, and agility, cicadas are an easy target for any hungry critter; even box turtles eat them! The way they persist from one generation to the next is simply to exist in such massive quantities that it becomes impossible for ALL of them to be consumed. In peak areas, periodical cicadas exist at a density of roughly 1.5 million per acre. This translates to about 25 per square foot! It also explains why the more squeamish among us are so freaked out by the sheer magnitude of the entire phenomenon; it truly resembles a real-life horror movie (although the bugs pose absolutely no danger whatsoever.)

Photo Credit: Michael J. Raupp, Ph.D., Professor Emeritus of Entomology and Extension Specialist at the University of Maryland Extension

- For those who question what role cicadas play in the ecosystem, what benefit they

provide, why they are here . . . scientists have found that many birds and small mammals receive a population boost in years of cicada emergence, as the bumper crop of

provide, why they are here . . . scientists have found that many birds and small mammals receive a population boost in years of cicada emergence, as the bumper crop of  available food leads to higher natality. The emergence holes dug by nymphs tend to fill in very gradually and thus help aerate the soil, leading to a healthier plant community. And, interestingly, the masses of exoskeletons and dead carcasses left at the end of a cicada summer provide nutrients for the very trees on which the insects had been dining, fueling the circle of life for the next generation!

available food leads to higher natality. The emergence holes dug by nymphs tend to fill in very gradually and thus help aerate the soil, leading to a healthier plant community. And, interestingly, the masses of exoskeletons and dead carcasses left at the end of a cicada summer provide nutrients for the very trees on which the insects had been dining, fueling the circle of life for the next generation!

Taken as a whole, the many peculiar and fantastical details of the biography of periodical cicadas weave a story so outlandishly strange that it’s largely inconceivable, even to those who devote their lives to the study of science. The greatest artistic and literary minds the world over could not have concocted a tale any more bizarre or intricate than that of the periodical cicada! It’s incomprehensible; and yet here we are, privy to it in our own backyards! But they’ll be gone in just a few short weeks, almost as quickly as they arrived. Relish this brief moment in time, because you just can’t make this stuff up. –BR