The Red-breasts are coming! The Red-breasts are coming!

With the temperature pushing 90o again, it’s difficult to even begin to think about winter wildlife, but, thanks to a surprise encounter yesterday, I have begun doing just that. My son and I took an enjoyable hike yesterday morning on one of our favorite wooded trails in Baltimore County. The trail, which begins at ‘Gate 4,’ roughly 2 miles west-northwest of the Prettyboy Dam, is a product of FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps from the 1930’s. It begins as a wide and easy-to-follow fire road, then forks into several smaller paths that ramble around one of the larger peninsulas of the reservoir. With its out-of-the-way location, it’s not a highly traveled circuit, but area birders know it well. Despite its location smack in the middle of the Maryland Piedmont, the lush, fern-laden forest understory provides perfect breeding habitat for several of our most colorful and sought-after warbler species. Specifically, stunning gold and black Hooded (below left) and Kentucky (below right) Warblers, both species with bold, explosive songs that seem to pierce through the forest underbrush, are easier to find here than in almost any other location in the county.

Much of the trail traverses mature deciduous

Much of the trail traverses mature deciduous  forest, where these two memorable songsters–and also Worm-eating Warblers and a plethora of Ovenbirds, not to mention larger non-warbler species such as Scarlet Tanagers and Yellow-billed Cuckoos–reside. Near the trailhead, there’s a pine stand interspersed with sun-drenched clearings, on the left-hand (northwest) side of the trail; this is home to bright yellow and green Prairie and Pine Warblers. On the opposite side is a large area of younger trees and

forest, where these two memorable songsters–and also Worm-eating Warblers and a plethora of Ovenbirds, not to mention larger non-warbler species such as Scarlet Tanagers and Yellow-billed Cuckoos–reside. Near the trailhead, there’s a pine stand interspersed with sun-drenched clearings, on the left-hand (northwest) side of the trail; this is home to bright yellow and green Prairie and Pine Warblers. On the opposite side is a large area of younger trees and  overgrown thickets, where Yellow-breasted

overgrown thickets, where Yellow-breasted  Chats and Indigo Buntings breed. Admittedly, all of these gorgeous songbirds can be found migrating through plenty of other woodland habitats for a few weeks every May; what’s unusual is that the CCC trail is one of the few places where they remain all summer long to raise their young. The eBird ‘bar charts’ more than explain this hotspot’s well-deserved reputation as THE

Chats and Indigo Buntings breed. Admittedly, all of these gorgeous songbirds can be found migrating through plenty of other woodland habitats for a few weeks every May; what’s unusual is that the CCC trail is one of the few places where they remain all summer long to raise their young. The eBird ‘bar charts’ more than explain this hotspot’s well-deserved reputation as THE  destination for local

destination for local  warbler-seekers. In fact, the previous time that Max and I hiked it (this past May), we saw no less than 41 warblers of a dozen different species. Even during the peak of spring migration, that’s quite a morning’s haul, but it was by no means unusual for the CCC trail. The variety and extent of the woodland habitats, proximity to a large body of water, and relative isolation seem to make this peninsula a popular stopover for birds passing through, en route to Canadian or New England breeding grounds.

warbler-seekers. In fact, the previous time that Max and I hiked it (this past May), we saw no less than 41 warblers of a dozen different species. Even during the peak of spring migration, that’s quite a morning’s haul, but it was by no means unusual for the CCC trail. The variety and extent of the woodland habitats, proximity to a large body of water, and relative isolation seem to make this peninsula a popular stopover for birds passing through, en route to Canadian or New England breeding grounds.

But what does any of this have to do with winter? I’m getting there . . . As you likely know, one of the main reasons that warblers are highly sought-after birds is how elusive they can be. They are among the smallest and daintiest members of our avian community, they rarely stay put for more than a few seconds, and they tend to forage either deep in dense understory vegetation or high in the forest canopy. When birders do encounter them, looks tend to be brief and photo ops few. To counter this, birders have ‘evolved’ the behavior of ‘pishing’–imitating,  through a closed-teeth airy hissing sound, the alarm calls of several common species of Parids (titmice and chickadees.) These observant species (Parids) act as the security guards of the forest, alerting others when a snake, fox, owl, or other potential predator is nearby, and their repeated scolding calls bring in a variety of other species who, collectively, harass predators away via a ‘safety-in-numbers’ type of attack. Many birders have mastered a perfect replica of this pishing and use it to bring in hard-to-see forest birds. A handful, my 21 year-old son among them, take it one step further. Max, a talented trumpet player and frequent whistler, has taught himself a flawless rendition of both the trilling call and the ‘whinny’ of the Eastern Screech-Owl. Not only have I seen him call in other owls at dusk, but he can put an entire contingent of songbirds on high alert; it’s a skill I wish I could learn, but mine are feeble attempts compared to his. [Important note: both pishing and imitating owl calls are considered birding no-no’s during high breeding season. During the months of June and July, most bird species are building nests, laying eggs, and feeding young; this is a high-energy and high-stress part of their life cycle. False alarm-induced agitations only take away from these crucial parenting duties and cause anxiety at a time when birds are already hyper-protective and in need of constant foraging to keep hungry little mouths fed. Please save these methods of calling in birds for other times of year, and use them sparingly.]

through a closed-teeth airy hissing sound, the alarm calls of several common species of Parids (titmice and chickadees.) These observant species (Parids) act as the security guards of the forest, alerting others when a snake, fox, owl, or other potential predator is nearby, and their repeated scolding calls bring in a variety of other species who, collectively, harass predators away via a ‘safety-in-numbers’ type of attack. Many birders have mastered a perfect replica of this pishing and use it to bring in hard-to-see forest birds. A handful, my 21 year-old son among them, take it one step further. Max, a talented trumpet player and frequent whistler, has taught himself a flawless rendition of both the trilling call and the ‘whinny’ of the Eastern Screech-Owl. Not only have I seen him call in other owls at dusk, but he can put an entire contingent of songbirds on high alert; it’s a skill I wish I could learn, but mine are feeble attempts compared to his. [Important note: both pishing and imitating owl calls are considered birding no-no’s during high breeding season. During the months of June and July, most bird species are building nests, laying eggs, and feeding young; this is a high-energy and high-stress part of their life cycle. False alarm-induced agitations only take away from these crucial parenting duties and cause anxiety at a time when birds are already hyper-protective and in need of constant foraging to keep hungry little mouths fed. Please save these methods of calling in birds for other times of year, and use them sparingly.]

Well, Saturday morning Max’s whinny was unusually ‘on.’ We kept hearing call notes of what we thought was a Kentucky Warbler, but the secretive skulker wouldn’t show itself, and we wanted to be sure. As Max started trilling, not only did that bird come forth, but warblers of four other species showed their faces, as well. Most surprising, however, was the tiny tin-horn tooting we heard from the tall white pines overhead. Sure enough, within a few  minutes, we had located not one, nor two, but three Red-breasted Nuthatches, a northern species of the coniferous forest that generally only appears in Maryland for several months every few winters. Red-breasts rank near the top of the cuteness scale, and their adorable squeaky ank-ank calls certainly

minutes, we had located not one, nor two, but three Red-breasted Nuthatches, a northern species of the coniferous forest that generally only appears in Maryland for several months every few winters. Red-breasts rank near the top of the cuteness scale, and their adorable squeaky ank-ank calls certainly add to the charm. As songbirds go, they are among the most specialized in diet; largely insectivorous in the warmer months, they switch over to eating primarily conifer seeds in the colder half of the year. As a result, the species is very closely associated with the cones of pine, spruce, and fir trees and rarely found far from them. These northern conifers are notoriously cyclical in their seed production; many years yield an abundance of cones, but others relatively few. Occasional major outbreaks of the Spruce Budworm only exacerbate the lean years.

add to the charm. As songbirds go, they are among the most specialized in diet; largely insectivorous in the warmer months, they switch over to eating primarily conifer seeds in the colder half of the year. As a result, the species is very closely associated with the cones of pine, spruce, and fir trees and rarely found far from them. These northern conifers are notoriously cyclical in their seed production; many years yield an abundance of cones, but others relatively few. Occasional major outbreaks of the Spruce Budworm only exacerbate the lean years.

The lemming-like fluctuations in Canadian cone crops is what leads to a handful of northern bird species being known as ‘irruptive’ in the United States. Along with the Purple Finch, Pine Siskin, Redpolls, Crossbills, and several species of Grosbeaks, the Red-breasted Nuthatch is largely a hit-or-miss species in the U.S. and it’s all dependent upon the availability of conifer seeds in the Great North. Many winters (last year, for instance) we see none of these birds; others years, we can be  inundated. In years of low seed production, most of the finches mentioned above travel from the Canadian taiga down into the Adirondacks and northern New England, where they suddenly show up at bird feeders in large flocks, after years of being absent. Sizable numbers may even appear in the Mid-Atlantic, as was the case with White-winged Crossbills in the winter of 2012-13 and Pine Siskins two years later. With Red-breasted Nuthatches, which are more solitary birds to begin with, irruptions take a different form, as they occur more often (seemingly every 3-4 years) and are much wider spread; typically, small numbers of Red-breasts begin to show up across most of the United States, as far south as the panhandle of Florida and northern Texas, in early or mid-Fall. Essentially their normal winter range extends in area five- to ten-fold, as they search for locations with plentiful food. Not surprisingly, the most noteworthy irruptions occur when an unusually good cone crop (which leads to higher natality and winter survival rates in the birds that eat them) is followed by a crop failure the following year.

inundated. In years of low seed production, most of the finches mentioned above travel from the Canadian taiga down into the Adirondacks and northern New England, where they suddenly show up at bird feeders in large flocks, after years of being absent. Sizable numbers may even appear in the Mid-Atlantic, as was the case with White-winged Crossbills in the winter of 2012-13 and Pine Siskins two years later. With Red-breasted Nuthatches, which are more solitary birds to begin with, irruptions take a different form, as they occur more often (seemingly every 3-4 years) and are much wider spread; typically, small numbers of Red-breasts begin to show up across most of the United States, as far south as the panhandle of Florida and northern Texas, in early or mid-Fall. Essentially their normal winter range extends in area five- to ten-fold, as they search for locations with plentiful food. Not surprisingly, the most noteworthy irruptions occur when an unusually good cone crop (which leads to higher natality and winter survival rates in the birds that eat them) is followed by a crop failure the following year.

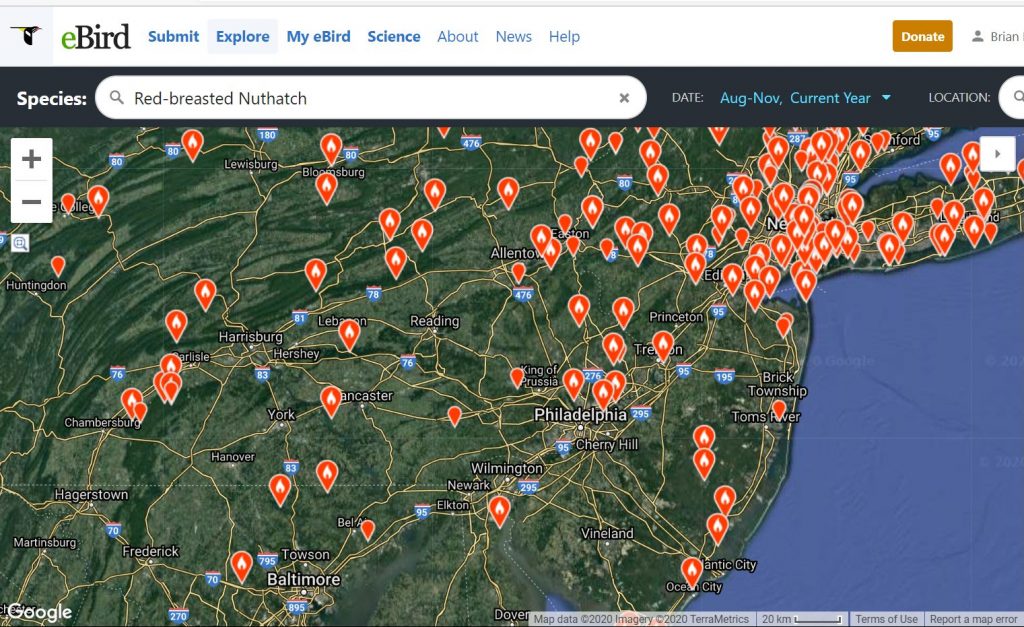

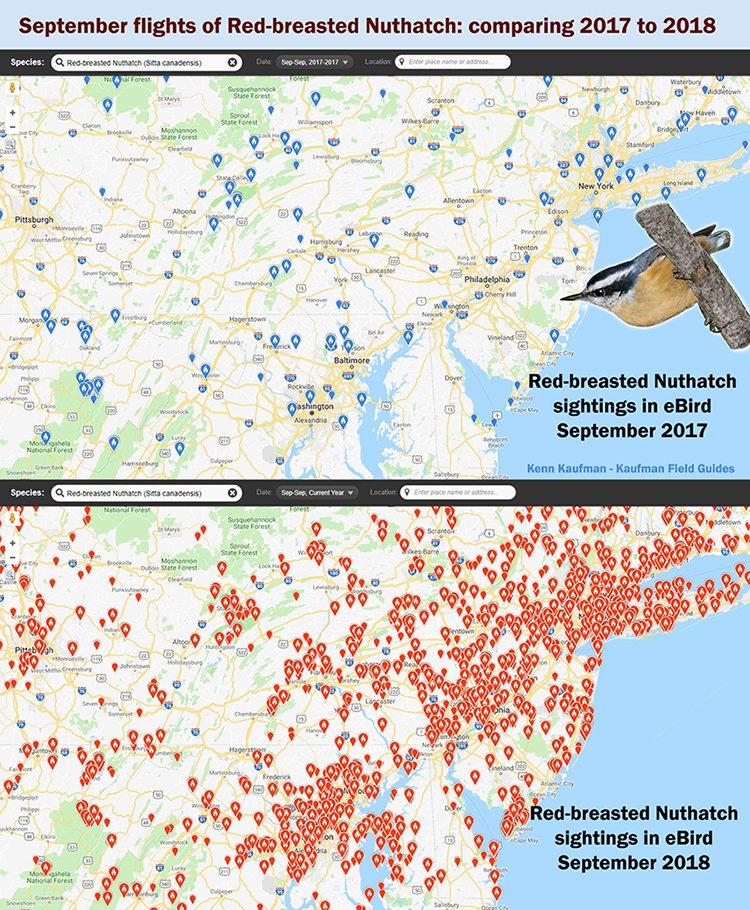

The most recent irruption of Red-breasted Nuthatches was just two years ago, in the fall of 2018. The dramatic nature of irruptions is easy to see, given the graphic capabilities of eBird reports. Compare the density of sightings (indicated by blue and red markers) in the Mid-Atlantic during these two consecutive Septembers, the first an ‘ordinary’ year in which almost all RBNU remained in Canada year-round, the second marking the beginning of our most recent irruption!

The most recent irruption of Red-breasted Nuthatches was just two years ago, in the fall of 2018. The dramatic nature of irruptions is easy to see, given the graphic capabilities of eBird reports. Compare the density of sightings (indicated by blue and red markers) in the Mid-Atlantic during these two consecutive Septembers, the first an ‘ordinary’ year in which almost all RBNU remained in Canada year-round, the second marking the beginning of our most recent irruption!

←

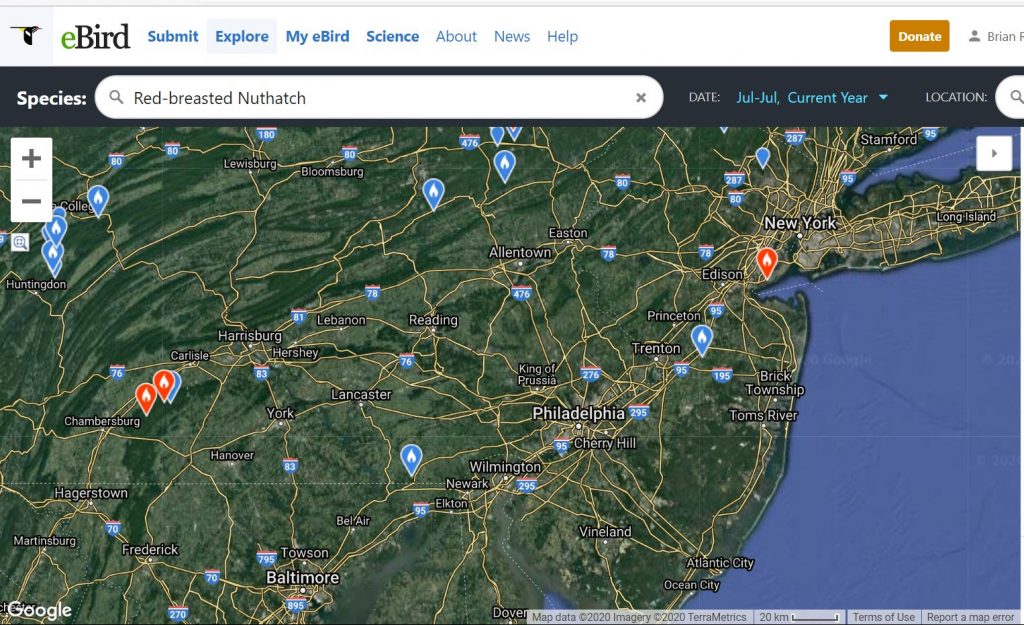

Personally, I’ve seen Red-breasts in the Baltimore area in the latter half of September during some previous irruption years, but encountering them already in August was a first for me. Until Saturday, I was completely unaware that we were on the doorstep of the next irruption. In fact, it wasn’t even on my radar, as we only had one down year since the last big influx. When I went to report our eBird checklist on Saturday, ‘our’ nuthatches were just the second report for the region this month (the first was a report two days prior near St. Michael’s on the Eastern Shore) and showed up as a ‘rarity’ which required further description and/or photographic documentation. However, I’ve since learned that ours was just one of four reports in Maryland on Saturday, and five more rolled in on Sunday. When I looked for recent sightings just to our north, I couldn’t believe the number of reports just over the past week from the Pocono region, northern New Jersey, and all around the New York City area. The two maps below tell the remarkable story of a very rapid (albeit temporary) range shift–the extent and speed of which is rarely witnessed in nature. To the left are reporting sightings throughout July of 2020 and to the right are the August reports (as of 8/23/20)–with still a week to go!

For a species that is generally NOT a long-distance migrant and is accustomed to living in cold northern climates, this sudden influx is not only a classic example of a major food-supply related irruption but it’s also occurring unusually early in the year. For those of you with bird feeders at home, this is great news–perhaps enough to convince others to go out and purchase feeders for the coming cold season! Chances are good that you’ll see these entertaining little birds a lot this winter, and the fact that they’re arriving already means you’ll enjoy hearing their amusing vocalizations while the windows are still open! It may–but not necessarily–also mean there are more avian surprises ahead; irruptions in one northern species often indicate others might follow, unless their alternate food sources are more abundant up north. The forecasting expert on this sort of thing is retired Canadian naturalist Ron Pittaway, who worked in Algonquin Provincial Park in the 1970’s and 80’s. There he became aware of the close correlation between summer cone crops and winter birds staying or heading south in large numbers. A founding member of the Ontario Field Ornithologists, Pittaway honed his observations into a bit of an art form, with the help of cone-related feedback from botanists and field ecologists in various parts of Canada. For over two decades now, he has released each fall a detailed prognosticating report that becomes referenced by bird enthusiasts all over the continent. The vast majority of ‘Puxutawney Pittaway’s’ predictions have indeed materialized. I, like many avid birders, always look forward to the release of Pittaway’s next report; they generally go public in mid-September. This year’s is still almost a month away, but one thing’s for sure . . . it’s going to be a big winter for nuthatches! Enjoy every minute with these little acrobats full of pint-sized personality; it’ll be at least several years before any of us experience an invasion like this again.