There’s an on-going joking banter between my wife and me. To be clear, she does not share my passion for waking up early, trudging through mud, tolerating mosquitoes and occasional ticks, and skipping lunch–all in the name of seeking to find unusual feathered fauna in unlikely places. Crazy her, huh? To be fair, she is generally a good sport about tolerating my obsession and has absorbed a fair amount about birds herself, largely by osmosis, since she’s surrounded by a family that ‘speaks bird‘ much of the time. Anyway, when we were young and childless, the patient SOB (see previous link) used to ridicule my use of the word ‘bird’ as a verb. Like many youngish men who weren’t particularly fond of the ‘little old lady’ stereotype associated with the term ‘birdwatching,’ I preferred the more hip–alright, at least slightly less nerdy, label-neutral, and abbreviated form of the word and insisted that I went birding. After all, experienced birders don’t just watch, they listen! Indeed, during the warmer half of the year, when deciduous trees are thick with foliage, serious birders identify far more species by ear than by sight. Learning to recognize songs and call notes is one of the more challenging aspects of the hobby and doing so reliably is a mark of serious time investment, lots of practice, and a keen ability to discern subtle differences in pitch, tempo, or cadence. The ability to correctly ID without seeing a bird is a source of real pride to young avian enthusiasts and often what separates die-hard birders from casual backyard birdwatchers. According to Merriam-Webster, the first use of the word birder came in the late 1800’s, only several decades after the origin of birdwatcher. Birding, as a verb, gained wide-spread acceptance in the 1970’s and dictionaries now reflect that ‘bird’ is no longer just a noun. There is similar agreement among almost everyone with any connection to ornithology that the difference between birding and birdwatching is simply one of degree, with birding being the more serious pursuit. (It is worth noting that William Shakespeare was way ahead of his time in using the term ‘birding’ to refer to waterfowl hunting–way back in 1602!)

Well, a similar grammatical teasing has been taking place in our household recently, as my sons and I have started using the word ‘atlas’ as a verb (e.g.,’Unless it rains, we’re going atlasing on Saturday morning.’) My wife points out, correctly this time, that dictionaries only refer to it as a noun. I reassure her that this, too, will change, pointing out the surprisingly rapid acceptance of the word ‘pish’, not just among birders, but in the greater community, since almost everybody knows a birder–or at least a birdwatcher–these days. I have to introduce new lingo to her gradually; were I to present the entire book of bird-speak all at once, it might pish, I mean push, her over the edge. Did I mention that my wife is a linguist? She’s fluent in French–and has taught it for three decades–semi-fluent in Spanish and conversant in German. I sometimes regret not following up with my own study of languages beyond freshman year of college. It’s made worse by the fact that my wife denies the very existence of ‘bird-speak’ as a second language. Little does she know how complicated and ever-evolving it’s become, thanks, in large part, to those fanatical twitchers in Great Britain. I’d like to see her find her way to the loo on a twitching outing to an unfamiliar RSPB nature reserve without a bird-speak translator.

The reason we are ‘atlasing’ is that we are participating in an exciting local citizen science project that recently started and will continue through the summer of 2024. The Third Breeding Bird Atlas of Maryland and the District of Columbia got underway this spring and maintains Maryland’s status as a national leader in this kind of geographically-based ecological research. Mapping out the distribution of birds on a national level began in Britain (of course) in the 1950’s and 60’s. Renowned ornithologist (and a former mentor of mine) Chandler Robbins adapted the process and organized the first atlas projects in the U.S., with county-wide efforts in Montgomery County, MD, from 1971-73 and Howard County, from 1973-75. Shortly thereafter, Massachusetts (1974-79) completed the first statewide atlas and was followed by Vermont then Maine several years later. As these early projects concluded and ornithologists began to appreciate the sheer volume of useful data that could be collected by amateur birders, not necessarily by scientists themselves, atlasing really caught on. Maryland’s first statewide atlas (1983-87) was one of eleven to be completed that decade; the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec completed atlases in the 1980’s, as well. Since, all but a few U.S. states have completed at least one five-year atlas project; many have completed two (Maryland’s second was completed from 2002-06) and most of them plan to reiterate the process roughly every 20 years as a means of detecting long-term population trends for each bird species. Maryland and New York are pacing the way, starting their third atlases this year. Maryland is also one of only a few states to have published both atlases in book form.

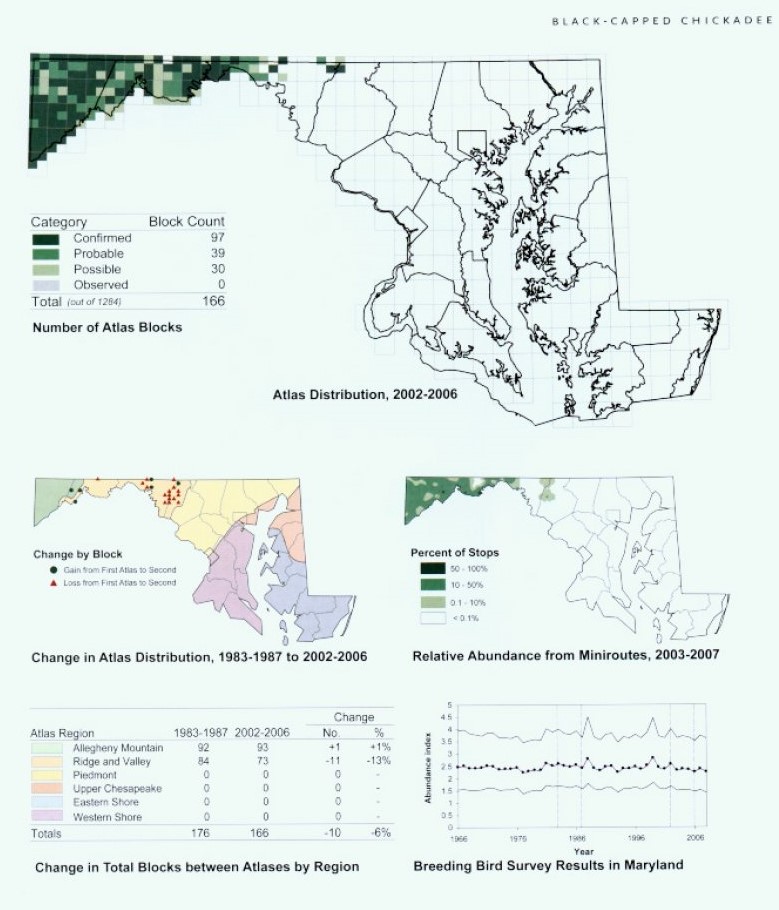

Now that protocols have been more or less standardized, the concept behind a breeding bird atlas is fairly simple, but the amount of effort involved is massive. Each state is split into a grid of rectangular blocks. In Maryland those blocks are roughly 9 square miles in size; there are about 1300 of them in the state. Each block gets assigned to a volunteer who becomes the ‘primary atlaser’ for that block. Of course, anyone can go birding in any block and can submit their bird data; however it is the responsibility of the primary atlaser to make sure that their block is getting appropriate coverage (at least 20 hours) and that all habitat types have been searched and all common and expected species documented. Data is collected over five consecutive years; the field season falls primarily in May, June, and July, when most bird species are nesting. In fact, to enter the database, each species must be observed during its specific range of ‘safe dates,’ to verify that it’s likely on breeding territory and not just migrating through. Depending on what behaviors are observed, each species is recorded with one of three breeding codes: either a POSSIBLE, PROBABLE, or CONFIRMED Breeder. To confirm breeding, one must actually see nestlings, eggs, an actively used nest, parents repeatedly carrying food to a particular tree or bush, etc. For some species (for instance, Robins, House Wrens, Tree and Barn Swallows), this is generally easy. However, for canopy-dwelling species, less vocal species, and uncommon species, it can be a real challenge. Still, records of Possible (a singing territorial male, perhaps) or Probable Breeding (that male singing in the same location for weeks on end) are almost as good. The overarching goal is to come out with a detailed map for each species, showing where it is believed to be nesting in Maryland, as a means of tracking changes over time.

With so many of these projects underway, scientists are already beginning to piece together atlases from neighboring states to get a more detailed picture of breeding range for some species. And, even though there have only been two iterations of the process, in Maryland already some fairly clear trends are emerging. To state the obvious (to anyone who has lived in the Old Line State for several decades), three large and easily detectable species happen to exemplify the most extreme population changes among any of our bird species. Keep in mind that these enormous shifts took place in less than two decades. Furthermore, they only reflect changes in the number of blocks in which breeding occurred, not the breeding density within those blocks. At least in the case of Canada Geese, their actual abundance has grown as fast or faster than their range expansion throughout the state.

With so many of these projects underway, scientists are already beginning to piece together atlases from neighboring states to get a more detailed picture of breeding range for some species. And, even though there have only been two iterations of the process, in Maryland already some fairly clear trends are emerging. To state the obvious (to anyone who has lived in the Old Line State for several decades), three large and easily detectable species happen to exemplify the most extreme population changes among any of our bird species. Keep in mind that these enormous shifts took place in less than two decades. Furthermore, they only reflect changes in the number of blocks in which breeding occurred, not the breeding density within those blocks. At least in the case of Canada Geese, their actual abundance has grown as fast or faster than their range expansion throughout the state.

| SPECIES | # of Blocks Reported in 1983-87 Atlas | # of Blocks Reported in 2002-06 Atlas |

| Ring-necked Pheasant | 412 | 101 (down 75%) |

| Wild Turkey | 231 | 725 (up 214%) |

| Canada Goose | 364 | 1056 (up 190%) |

For the vast majority of species, however, the changes from one atlas to the next are far less dramatic–up 4%, down 7%, . . . But if those changes continue–or accelerate–there’s a story to be told and, perhaps, addressed. Having detailed maps, not just for each county, but on the fine-grain level of every 3 mi x 3 mi block, is crucial for monitoring even subtle changes in species distribution. By knowing exactly where ranges are expanding or contracting, biologists can dig into potential causes–even very local ones (changes in logging practices within a state forest, diversion of a particular waterway, alterations in agricultural land management, introduction of an invasive pest species, elimination of a predator, and so forth)–and devise site-specific conservation plans to halt the trend. This is why the BBA3 project needs you!

One does NOT need to be a seasoned birder to contribute to the atlas. Some blocks in our region are being heavily scoured, but others have received very little coverage thus far. Current data for the block containing Irvine can be found here. This time of year, in particular, when nestlings are fledging and parents are feeding hungry mouths non-stop, even a walk around your neighborhood can lead to valuable confirmations of breeding. Any data submitted will be helpful. One doesn’t need a complete list of all species encountered, nor to know in which block one was birding. The Third MD/DC Atlas is, for the first time, being managed entirely electronically, on eBird, and the data-entry process is simple and seamless. So, keep your eye out for nests, baby birds, species heading in and out of the same bush dozens of times a day, and share your findings so they can be incorporated into the atlas. Take a few intentional walks, just to look for signs of breeding birds; even plan ahead and check which blocks need more coverage and find a suitable strolling site within them! You may find that you enjoy this form of citizen science so much that you’ll want to offer to become a primary atlaser for one of the unclaimed or less-visited blocks! Whether you view yourself as a twitcher, birder, birdwatcher, or general nature appreciator, atlas is a verb you should add to your vocabulary.